Delivering a Presentation

| Site: | Poznan University of Technology |

| Course: | Unit 5: Delivering a Presentation |

| Book: | Delivering a Presentation |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, 24 January 2026, 4:32 PM |

PUBLIC SPEAKING

Visual aids

You may want to use visual aids throughout your speech to help the audience understand the point you are making. Visual aids come in many different forms, the main ones being: graphic (graphs and charts), three-dimensional and projected aids.

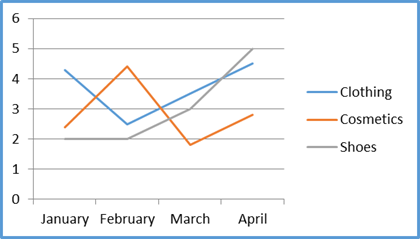

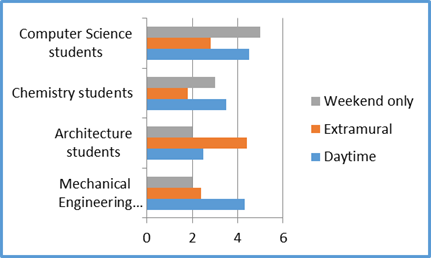

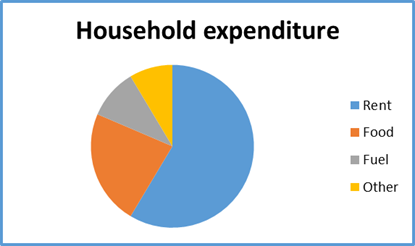

Let’s look at some examples of graphic aids. Charts and graphs are mostly used to show numerical data. When using them, be sure to double check your numbers!

Fig. 5.1. Line graph: Sales in a major American department store

Fig. 5.2. Bar graph: Average student hours of absence per semester

Fig. 5.3. Circle graph (pie chart): Household expenditure in Britain in 2015

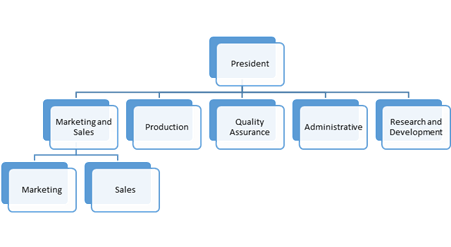

Fig. 5.4. Example of an organization chart of a company

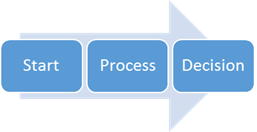

Fig.

5.5. Example of a flow chart

When you want the listeners to participate in your presentation, flip charts are the best (you can add others’ responses or ideas). You need to remember, though, that in order to use them, you need to be able to write clearly. Do not cover the whole sheet with your text; do not use too many colours, or too many words. You can draw, add human figures, and make it more interesting. You may even prepare a flip chart in advance, leaving room for additions. However, flip charts are not good for large audiences: you need everyone to see what is on the chart clearly.

Another group of aids, three-dimensional ones, can be full-scale objects or models presented to the audience. They could be almost anything, from a first-aid kit to a small-scale model of an office building.

When it comes to projected aids, the most popular nowadays seem to be computer-generated slides (e.g.: Power Point or Prezi). When using such aids, you have to remember not to flip the slides too often (allow at least 20 seconds for your audience to view each slide). Also, do not prepare too many of them for the length of your presentation.

You need to carefully choose the proper visual aids for your presentation, and decide which form they are going to take: handouts for everybody present (distributed before or after the presentation) or other visual aids used during the presentation. When it comes to handouts, usually everybody loves them and wants them. However, it is for you to decide how much information you are going to include on them. As with all facts, check lists and data. Also, think when you want to give them out. If they contain information needed during your presentation, you will distribute them in the beginning or at a particular moment in time. If they summarize your speech, you may want to wait until you end your presentation, so that they do not become an unnecessary distraction.

Visuals as such do not necessarily improve your presentation; they have to be carefully chosen to achieve the effect you want. Whatever the aids, make the text large enough, keep it simple and check for spelling errors. Remember not to talk to your visuals when presenting them: always face the audience.

Note

Note

A NOTE ON POWERPOINT AND PREZI

If you want to use PowerPoint or Prezi software with your speech, be aware of their shortcomings, and do not let them take over your presentation. Sometimes PowerPoint and Prezi tend to emphasize form over content, making the message seem less important. They also keep the presenter from contacting the audience, because everybody is just interested in the slides and not the speaker. The audiences nowadays seem to expect PowerPoint and Prezi presentations. If you decide to use them, here are a few things to remember:

- keep the style simple and the text large enough to read

- check spelling

- do not use too many bullet points on one page

- do not ignore your audience by concentrating on your slides

- do not read from your slides

- talk about what the audience can actually see at a given moment

- you still need to practice your presentation.

Final preparation and rehearsal

Now is the time to write notes for your delivery of the speech. Make sure to note down all the important quotations, facts and figures, and any information you may not remember, but do not write down entire sentences to be read. The best size of your notes is half the size of a European A4 page. It lets you note down only the main ideas, but also does not distract the audience, who will be watching you turn big sheets of paper.

Choose the style, i.e. words carefully! Use simple language, keep sentences short, be specific, and avoid clichés. You want everybody to be able to understand you so avoid using technical jargon. In some cases, however, using a field-specific language can create a bond between you and your audience. For example, computer science students may feel at ease and follow happily a presentation by their colleague. The same presentation given to students of law may lead to misunderstandings and frustration of the audience.

When it comes to using humour, a presenter needs to be very careful, especially when talking to a group of people he or she does not know well. It is better to avoid humour altogether than end up with a very embarrassed audience!

You want to be enthusiastic when speaking but also comprehended well. Therefore, you will need to check the pronunciation of certain words beforehand, and work on speaking at a normal rate, making pauses at appropriate places and adjusting the volume of your speech.

Finally, when everything is carefully planned, it is time for you to rehearse your speech. If possible, you might ask a friend or a family member to listen to you and give you their feedback. If not, record your speech or speak in front of the mirror. Apart from obvious advantages, the actual speaking process also lets you check the time limit and minimizes stage fright. You may want to pay special attention to your posture and movement, gestures and eye contact.

Posture should be straight but relaxed. Do not lean on anything, do not sway, and do not fold your hands in front or back. Vary your gestures and adjust them to the size of your audience. Watch out for things you do unconsciously (you could make a video of yourself speaking, if possible). Do you know that you always scratch behind your left ear when asked a difficult question?

Different cultures will approach public speaking differently. Remember that Europeans prefer a more formal style of presentations than Americans; they do not like a lot of walking or gesturing during presentation, and they usually stand during speech making. North Americans prefer an animated style of presentation (bigger gestures). They also make eye contact during the last few words of a sentence and then hold it for a second or two.

In general, you want

to maintain eye contact with individuals in your audience, not just one spot.

Also, dress conservatively, wear clean comfortable shoes, and do not play with

your pencils while speaking. Remember to smile.

Note

Note

A NOTE ON FIGHTING STAGE FRIGHT

Most people experience some sort of anxiety when speaking in public. It may be because they present to an unknown audience, or because they really want to impress their boss, or because they want to sell something very badly. There are several ways to deal with the kind of stress. First of all, remember that your audience does not know that you are nervous. Second, you have all the necessary knowledge to make your presentation a success. Third, a little bit of stress is good (the same way an athlete is helped by the adrenaline rush).

So, minimize the

problems by preparing well, rehearsing the speech out loud, anticipating

questions you may be asked or any other problems that may arise. Think what you

can do to solve them.

Final piece of advice

If you have decided to conduct a question-and-answer session at the end of your presentation, you should prepare for that, too. You may be able to anticipate some of the questions, and thus think about the answers beforehand. As with the whole presentation, you are in command and should not let a few people dominate the whole session with their questions or speeches. Be polite but keep your answers short and to the point (which is your presentation). If a question surprises you, you may want to repeat it first (to make sure everyone has heard it and that you heard it correctly). It will buy you a little time in which to prepare your answer. If there is no time to answer all questions, you may finish the session by giving the audience your email address. They will send their questions directly to you. As with the main body of your presentation, you should end your question-and-answer session strongly and on time.

When all is said and done, be sure to arrive early at the place where you are to speak and check the apparatus. Is the microphone working? What about your laptop? Where will you stand?

Other things to check before you start:

- how to get there

- room layout

- seating arrangements

- audio-visual equipment

- sound system (what kind of microphone will you have: built-in podium mike, hand-held mike, lapel mike, wireless mike?)

- location of electricity outlets

- podium (if there is any)

- lighting

- location of restrooms

- temperature and ventilation.

We said in the previous chapter: No matter what the subject matter of the speech might be, a good speaker needs to have integrity, knowledge of the subject and skill in presenting it (DLI, 1996).

To put it differently, if you have integrity the audience will believe you; if you are interesting they will listen, and if you know the subject well they might even learn from you! And, as with every skill to be learned, your public speaking will improve with practice – practice makes perfect.

(Text adapted from the book: Introduction to Interpersonal Communication, Szczuka-Dorna L., Vendome E., Poznan University of Technology, 2017.)

Essential Vocabulary

Essential Vocabulary

Outline (noun) – a summary of a written work or speech, usually done in headings and subheadings

Persuasive (adj.) – having the power to persuade

Reference (noun) – note in a publication referring the reader to another passage or source

Rehearse (verb) – to practice in preparation for public performance

Shortcoming (noun) – a flaw, deficiency, defect

Stage fright (noun) – acute nervousness associated with performing or speaking before an audience

Transition (noun) – a word, phrase, sentence connecting one part of discourse to another